Process is a very important part of how I work. I once described myself as a chemist working in wood. I said it to a chemist. I don’t say that anymore. I’m interested in reactions. The reactions that come from chemicals colliding with other chemistries already present in the material. While most of this happens later in the process for finish and coloration, it guides and informs the rough stages through to the final mark-making. How will the intended reaction affect a rough, faceted area versus a smooth polished one?

The assembled wood panel is the starting point, a blank canvas for lack of an original term. I spend a lot of time drawing directly on the surface, building up lines and curves and refining them. Comparison back to the original sketch shows a great deal of difference. The wood species is chosen for the same reasons of reaction; Is it light or dark? Does it contain acids suited to the intended result? Is it right for the kinds of marks to be made?

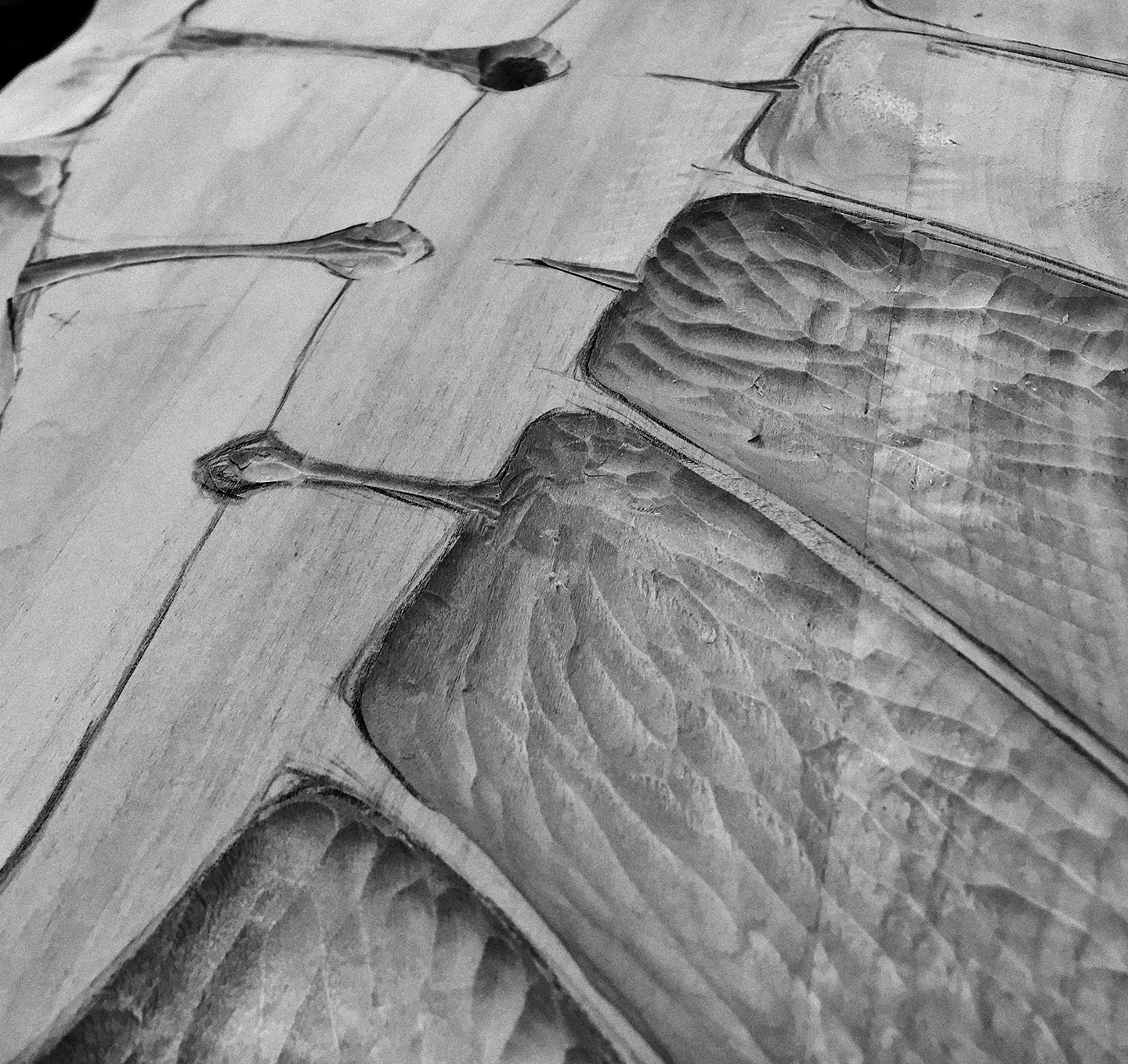

When a sketch is finalized and the panel is ready to be worked, large areas are addressed using whatever device is at hand and capable of fast and accurate material removal. This is in no way an artistic step; it does give a first glance at what lies beneath the planed surface. It allows time to think about grain complexity, direction, and problem areas. Once complete, a whole new level of on-panel sketching is required so that thoughts from the original drawing are not lost and issues are resolved. Now drawing on a real topography, I’m able to start to see where the piece can go.

This is where the process really starts. Having gathered a variety of hand tools, I’m able to work on the topography in the way that suits me. The way I imagined in the years trying to take the step to do this instead of just think about doing it. I have considered the possibility that I am just making the work that suits the tools and methods I want to use. I’m not sure it matters.

My two competing interests can exist together in this process. My attraction to heavily textured, manipulated surfaces can be satisfied in this subtractive approach using carving, gouging and burning. The opposite track can be satisfied by the additive approach; build up a frame or armature to affix a wood skin to. Stretching and bending wood over a frame introduces tension and form hard to find in any other way. Once the form is complete, work the surface to apply color and texture.

At a technical level, I have settled on a small variety of wood species. The results that can be achieved in richness and color of Red Cedar are worth the amount of dust necessary to get there. Linden, while not as interesting in grain or color lends itself to the most pleasant way to spend a day with a chisel. Other species include Spruce, Cherry and Maple. I don’t really have a use for commercial stains, colorants or finishes. Most color is derived from the afore mentioned chemical reaction approach. Prior to the availability of commercial stains in cans on store shelves, carpenters and cabinet makers relied on chemical stains. These compounds could be risky to use and inconsistent in results. I have only scratched the surface of what is possible, but I have what I need. Tannic acids, either naturally present in the wood or added, confronted with an oxidation solution results in a range of grays, blues and browns much more natural in appearance than anything available in a can. Selectively masking areas from reaction by using solutions to remove tannins completes the coloration process. Final finish coats are applied that may include additional coloration or toning by adding dry earth pigments, wax, rust and other compounds.